The African American Experience at Hanover House

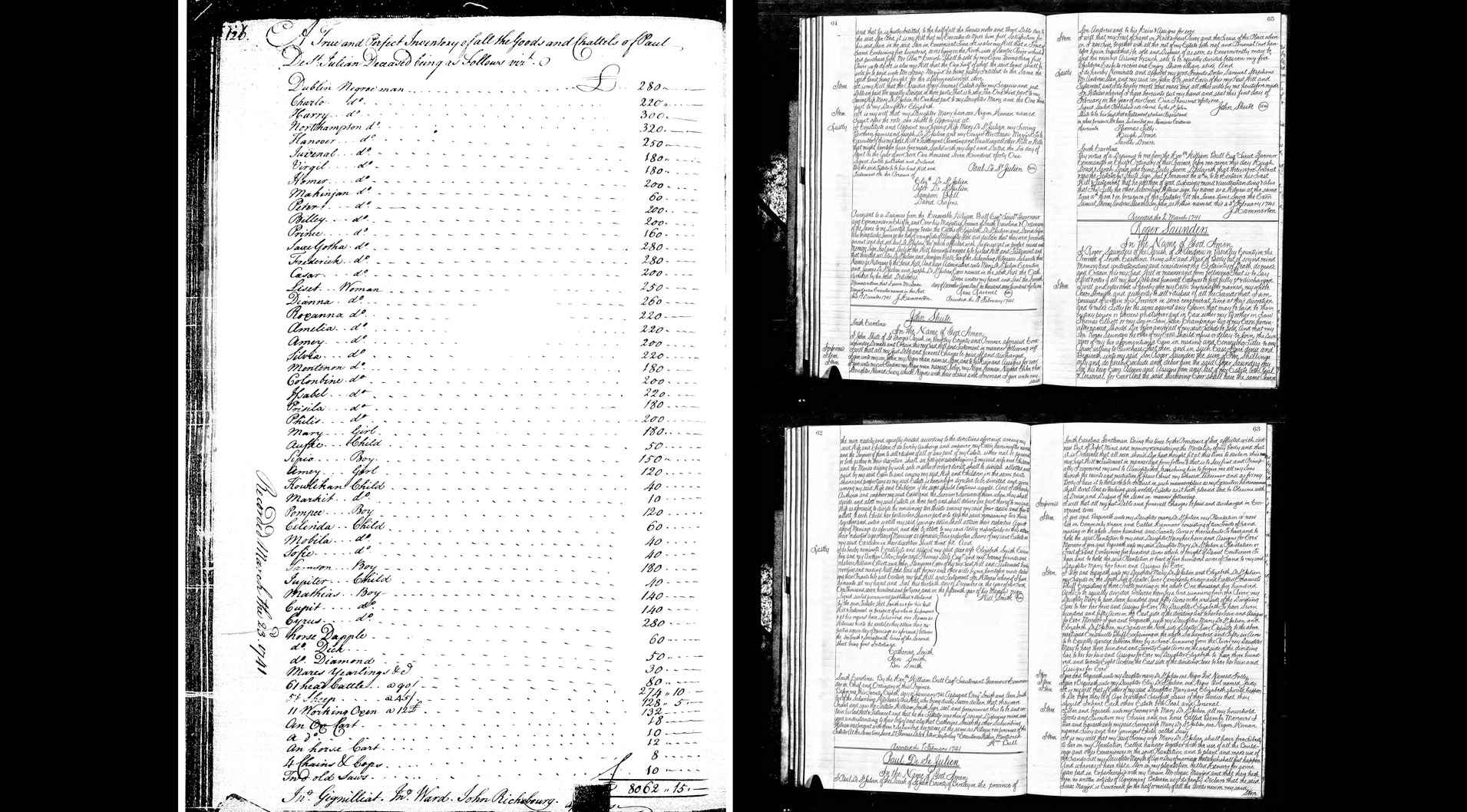

The African Americans at Hanover House from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries have left no known written records, documenting their lives and families in their own words. The only surviving records are scant, and they are primarily legal documents, last wills & testaments, inventories of estates, and census records.

In 1741, Paul de St Julien wrote his will, and he names five of the enslaved African Americans at Hanover. At the time of his death, there are 45 enslaved persons at Hanover. Between his will and the inventory of his estate, we do know the names given to the enslaved by Paul; however, we only know one familial relationship of Lucy and her youngest child Susy.

of Paul de St Julien

Dublin, Charlo, Harry, Northampton, Hanover, Juvenal, Virgil, Homer, Mahinjan, Peter, Billey, Prince, Saxegotha, Frederick and Casar were the men tasked with creating the rice fields from the swamplands, planting the crops, and any other assigned needs of the family.

Lucy, Liset, Dianna, Roxanna, Amelia, Amey, Silvia, Montenon, Colonbine, Issabel, Prisila and Philis were the women who would have harvested the crops and performed other assigned duties.

Folly, Judy, Susy (youngest child of Lucy), Mary, Aufie, Sipio, Amey, Houlihan, Markis, Pompee, Celinda, Mobila, Sofie, Samson, Jupiter, Mathias, Cupit and Cyrus were all children.

We do not know the ages or origins of the enslaved African Americans nor does the inventory list the gender of all the children.

We do not know the ages or origins of the enslaved African Americans nor does the inventory list the gender of all the children.

These enslaved persons may have been from the West Coast of Africa, known as the “Rice Coast.” These Africans had the expertise of planting, harvesting and processing rice, These enslaved laborers were tied to the 720 acres of Hanover for generations, growing wealth and status of the white families.

As the land was inherited by Stephen Ravenel from his father Henry, so too were the enslaved African Americans. Although the status and wealth of Hanover was made possible only through the labor of these African Americans, their names, families, and aspects of their lives are lost to history, unrecorded by the white families who enslaved them, except for those whose names appear in the wills, forever bound to the land and extended Ravenel families.

When Stephen signed his will on July 14, 1817, he named fifteen of the enslaved persons, whom likely labored and lived at Hanover. Gibby, an African American boy, was the first enslaved person named, and Gibby alone is given to Stephen’s brother Henry Ravenel. Daniel James Ravenel, who would inherit Hanover property, also inherited Jenny, Abram, Dick, Market, Wilson, Charley, Pleasant, Molly, Cain, Mary, Cuffey, Old Clafs, Sue, and Daniel, most likely all tied to Hanover’s 720 acres. Nephew John inherited Stephen’s “waiting man named Brafs,” and the other enslaved persons owned by Stephen Ravenel are unnamed nor counted; Stephen wrote “All the rest of my negroes not herein before given & devised, I give & bequeath to my brothers Rene and Paul to be equally divided between them.” This will made no mention of keeping enslaved families together nor are there any explanations for how his decisions were made to separate Gibby or Brafs or to divide any of the other enslaved African Americans between his male relatives.

Daniel James Ravenel also had no heirs, and in his will, dated on June 29,1836, he named only one enslaved person in specifically. Philip is described as “my Mulatto Boy Slave” by Daniel, and Daniel required that his Executors send Philip “out to a trade and if possible to give him his freedom.” There are no known records that give us information on Philip, who his parents were, or what was his fate.

All of the enslaved persons owned by Daniel are tied to the either his Brunswick Plantation or Hanover Plantation; Daniel bequeathed to his nephew Benjamin P. Ravenel Brunsick “with all lands adjoining thereto with all the negroes thereon” and if Benjamin died without heirs, then Daniel’s grandnephew would inherit the above mentioned. Hanover “with all the lands adjoining thereto with all the negroes thereon” were left to Daniel grandnephew Henry LeNoble Stevens, the last of the antebellum owners of the enslaved African Americans who were tied to Hanover. If Henry did not reach the age of 21 years old, then Daniel’s grandnephew William P. Ravenel would have inherited in Henry’s place.

Henry LeNoble Stevens enlisted and died serving the Confederacy. His daughter Henrietta LeNoble Stevens White eventually inherited Hanover property; however, how emancipation changed the lives of the enslaved persons at Hanover is unknown today. For the enslaved at Hanover, few times only the names at one brief snapshot are known, and only the familiar relationship of Lucy and her youngest daughter Susy was documented by Paul de St Julien in his will.