Marine biology in South Carolina

"You think, when you’re in high school or just starting out in this field, that science is set in stone. But the point in science is there are some things you just don’t know. That’s why you’re doing science in the first place."

Imagine if your best job ever could be the one you got while you were still in college.

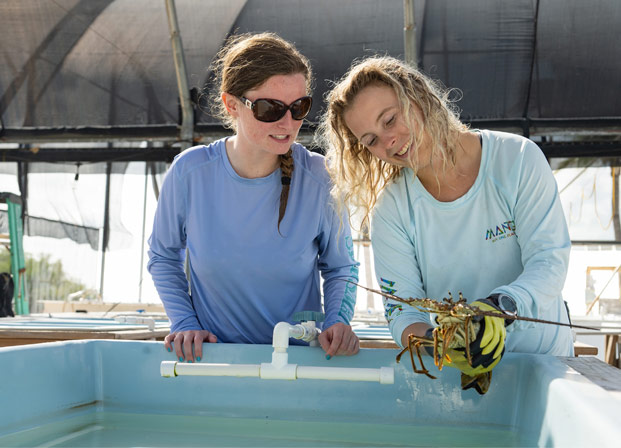

Clemson senior and Greenville, South Carolina, native Erin Griffin doesn’t have to ask if this is possible. Much to her surprise, she experienced the answer this summer in the small Key West town of Layton, Florida. There, at a waterfront marine research station — where she lived and worked with her professor and a team of other student biologists — she pursued answers about the ocean and its inhabitants.

She found her passion … and a career she can take anywhere.

Did you know?

Clemson is R1 Classified as one of the nation’s most active research institutions,

Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education.

Science: a team job

Science: a team job